Shortly after midnight on April 7, 2005, a young blond-haired man wearing a dark suit and white shirt was found wandering, dripping wet and distressed, near a beach at Minster on the Isle of Sheppey in North Kent. The police who picked him up couldn’t get a word out of him, so they conveyed him to the Medway Maritime Hospital on the mainland in Gillingham, where he was kept for a while and eventually sectioned for his own safety. He refused to speak, and became highly agitated when approached. He had no identification on him, and all the labels had been cut from his clothes. The clinicians made no progress with their nameless patient until, on being given some paper and pencils, he made a drawing of a grand piano. Taken to the piano in the hospital chapel, he sat down and played, much to the amazement of his carers, who recognised snatches of Swan Lake in his performance. Over the following days they encouraged him to play more, presenting him with sheet music of Lennon & McCartney tunes, and admiring the ease with which he played them at sight. They decided this troubled young man might actually be the real thing: a brilliant pianist, who had suffered some sort of breakdown and turned up on Sheppey dressed, so conjecture now suggested, as if he had walked out of, or fled, a perhaps disastrous performance. It was thought that the mystery man was probably British, and that there might be an orchestra or music academy somewhere that was missing a pianist. Such was the intention with which news of his situation was relayed to the press as well as to the National Missing Person’s Helpline.

It was the Mail on Sunday that triggered the explosion of interest. An article, published on May 15th, introduced this ‘silent genius’ to the world, and dubbed him the ‘Piano Man’. Speculation was intense, and the story of this man who had apparently risen from the sea was taken up almost instantly all over the world. Journalists and television crews from far-flung places advanced on the Isle of Sheppey: ‘This is really bizarre, no. . .’, muttered the local reporter from the Sheerness-Times Guardian as he pointed out a Tokyo television crew for a French journalist (Le Point, 26 May). There were some, including the duly interviewed manager of the pub on the road where the Piano Man had been found, who maintained the downbeat view that the stranger was just another illegal immigrant: either he had jumped off a passing ship, or been pushed into the water by people smugglers as they were approached by coastguards or the police. Such dark suspicions lurked in the back of some newspaper minds too, but the drama would soon be removed from its desolate location on the Isle of Sheppey, and relaunched as a universal ‘story’ about the identity, existence, loss and, in words attributed to an interested Hollywood producer by the Guardian, ‘the fragility of the human mind’ (Guardian, May 18). Here was a story that proved the proximity of art and reality, or so it seemed to the novelist, Chris Paling. He wrote an article for the Daily Telegraph (20 May), claiming to have written the Piano Man’s story already in his just published and duly advertised novel, in which a forgetful man crawls out of the sea and heads into a nearby town.

As the story spread throughout the summer, the Piano Man was the subject of a great efflorescence of speculative theories in which the suspected illegal immigrant and NHS scrounger was displaced by a tortured artistic genius who must have suffered some sort of nervous breakdown after a disastrous performance and not even had time to change out of his concert clothes before stepping onto the boat from which he would leap, distraught, as it approached the Thames estuary. Meanwhile, the search for the mystery man’s identity produced a dizzying array of contenders – many hundreds of them. There was a performance artist who had been seen in France or Spain, a classically trained pianist who had once played in dissident rock tribute band in Prague, a Canadian drifter known as ‘Mr. Nobody’ who had once tried to enter Britain illegally. Various women announced themselves quite certain the Piano Man was their missing boyfriend or husband. The man himself had by now been transferred to the Little Brook hospital in Dartford, where the Sun tried to donate a keyboard for his room. His ‘story’ was said to be of interest to so many Hollywood producers that, if Mark Lawson was to be believed, doctors and carers could hardly get through the crowd at his bedside (Guardian, June 18). There was also a flurry of armchair diagnosis. One psychiatrist, who had never met him, was in no doubt that the Piano Man had been hurled into a ‘fugue state’ by trauma. Pop psychologists also took to print to throw in their pennyworth – Oliver James was in very little doubt that the Piano Man was suffering from a ‘borderline personality disorder’. Dr Judith Gould of the National Autism Society diagnosed him as one of theirs. As the legend grew it became carrion for the meta-commentators too. The pop-Lacanian analyst, Darian Leader, speculated in the Times about how the story had activated ‘the common fantasy of escaping a humdrum existence’ (Times, May 21).

By the time the tide turned, the doctors and nurses at the Little Brook hospital had been caring for the Piano Man for the best part of four months. By late July, they were said to be wondering whether their patient’s voice box was damaged, or had even been removed, but were impeded by the difficulty of getting his formal permission for an endoscopic examination. On August 8, the Independent reported that doctors were worrying that ‘the talented musician in a wet suit’ might never be identified. But this all came to an abrupt end on the morning of Friday August 19, when a nurse went into his room and asked routinely, ‘Are you going to speak with us today?’ Unexpectedly, the Piano Man had opened his mouth and replied ‘I think I will.’ He went on to identify himself as a 20-year-old Bavarian, who, far from stepping out of the sea, had come to England by Eurostar from Paris, and had been trying to kill himself in the hours before he was picked up by the police. Informing the hospital staff that he had two sisters and was gay, he also announced that – as the hospital chaplain had himself suspected – he really could not play the piano particularly well at all, and that he had only drawn one because ‘it was the first thing that came to mind’.

By the time news of his recovery reached the press, Andreas Grassl was back with his dairy-farming parents in the tiny village of Prosdorf in Bavaria, whence he would only speak in carefully measured statements issued through the family’s solicitor. He explained that he had known nothing of the media storm brewing up around him, and, having thanked the psychiatrists and nurses who had looked after him, and also the many sympathetic people who had written to him while he was in hospital, he now had to think about his future. He wanted no more contact with the media. By the time the gay news service Pink News revisited the story two years later in 2007, Grassl was living in Basel, Switzerland, and studying French Literature at the university. By then reporters had found various of Grassl’s former friends and acquaintances who spoke of the difficulty of growing up gay in a conservative Bavarian village, and who declared that his crisis was said to have become acute in the French coastal town of Pornic, in South-Eastern Brittany, where a relationship had gone wrong.

The British press was by no means unanimously content to have its summer fantasies about the Piano Man so rudely interrupted by reality. Some commentators used merely plangent terms to express their disappointment at the sudden disenchantment caused by Grassl’s recovery. Writing in the Independent, Charles Nevin, who claimed to have dreamed that the piano man was another genius like Paderewski, regretted that ‘a little touch of magic and mystery is no more’. Other papers – and not just the tabloids – reacted as if they had been grievously let down by Grassl, who had proved quite unworthy of the celebrity they had so generously bestowed upon him. He was multiply denounced as a ‘fraud’ for not being mute and as a ‘sham’ for not really being able to play the piano well either. It was now said that his ‘glorious, enchanting music’ (Darian Leader) had actually consisted of ‘hitting a single key repeatedly’. Grassl was nothing but a ‘suicidal gay German’ and ‘just a fiddler’ who had made disreputable use of past experience as a ward orderly in Germany to act mad and freeload on the NHS. Various papers gleefully declared that the Health Authority were considering legal action to recover the costs of his care, but this wishful recommendation went nowhere – partly, as may be surmised, because the clinicians never doubted that Grassl had been in the midst of a crisis that was now successfully resolved.

Many of the loftier commentators, who offered the world their thoughts on the interest Grassl had accidentally generated, shared the assumption that the Piano Man was powerful because he represented what Darian Leader called a ‘blank canvas’ on which people could project their own longings and fantasies (Times, May 21). In reality, ‘canvas’ was not the medium that supported the billowing clouds of speculation, and neither was the screen on which they were projected in any way ‘blank’ .

In the words of the Sunday Telegraph, the story of the Piano Man was ‘strangely cinematic, from the shock of his dyed blond hair to the unusual formality of his attire. He is a walking plot yet to be unravelled’. (ST May 22) In the early weeks that ‘unravelling’ took several different forms, each one suggested and confirmed by a different film. Many, including some of his carers, saw the Piano Man through the prism provided by the Australian film Shine (1996) – which turned the tormented pianist David Helfgott into an embodiment of what one American psychiatrist diagnosed as ‘movie madness’: i.e. a ‘celluloid amalgam of schizophrenia, manic-depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and idiot savant’ (Kenneth Paul Rosenberg, M.D., letter to the editor, New York Times, March 15, 1997). For those inclined to emphasise the ‘autistic savant’ in this mix, further corroboration was provided by Dustin Hoffman’s performance as Raymond Babbitt in Rain Man (1988). A French writer, Jerôme Cordelier, who visited Sheppey for Le Point, added a more recondite film – The Man without a Past (2003) by the Finnish director Aki Kaurismäki, the hero of which is a welder who loses all knowledge of himself after being beaten up and robbed a few hours after arriving in Helsinki, and then builds a new life among the city’s container-dwelling outcasts. In Germany commentators reached further back to Werner Herzog’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974), in which a disorientated and more or less mute young man walks into early 19th century Nuremberg, having apparently been raised in total isolation from fellow humans.

However, the pictures that really kept the Piano Man aloft as he was pushed and pulled through this seething chaos of contending plots and scenarios were of a decidedly static and unmoving variety. A Kent-based ‘photojournalist’ named Mike Gunnill, has described how he got a call from the picture desk of the Daily Mail informing him that ‘a man has been found, he isn’t talking’. The Mail had been alerted to the story by an authorised social worker at the Medway Maritime Hospital in Gillingham, who explained that the ‘mystery man’s’ carers needed help in identifying him. On May 6 Gunnill visited the hospital and tried to photograph the unknown figure, but it quickly proved impossible – ‘he just covered his face every time and started to become distressed.’ A French reporter quotes Gunnill as saying that the man ‘screams and cries like a baby when he sees someone new’ and that he looked around ‘as if seeing the world for the first time’ (Le Point, May 26).

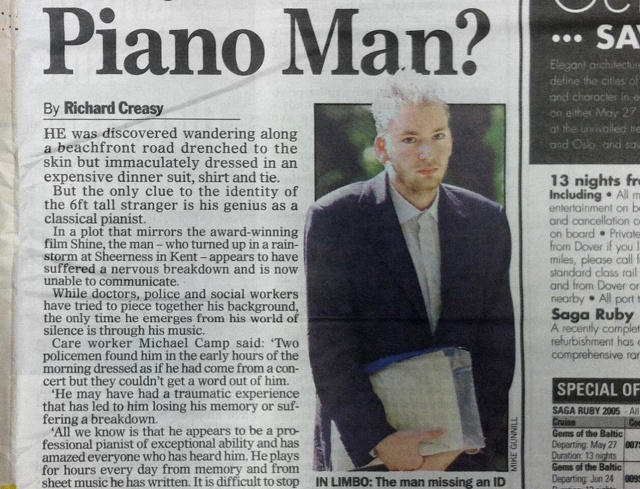

Realising that Gunnill might fare better when he took the man for his daily walk, the social worker, Michael Camp, took Gunnill out and showed him a place ‘partly hidden by trees’, and told him to be standing there and ready with his camera at the appointed time. Gunnill, who was effectively working as an NHS-assisted paparazzo, managed to get a few pictures before ‘the mystery man’ noticed his lens and took evasive action. They show Grassl as a frail, lightly bearded figure, with somewhat spikey blond hair, wearing his by now dried-out suit and white shirt, with every possible button done up. In one of Gunnill’s stolen shots, the solitary figure sees the camera and stares back with what may be a mixture of fear and disgust, clutching his plastic folder of music in both hands. In others he shields his face completely with the folder, or peeps out with one fiercely bright eye.

In the most evocative example, a cropped version of which was used by the Mail on Sunday to accompany the article of May 15, in which Grassl was first converted from ‘silent genius’ to ‘Piano Man’, he is all there from head to toe: tall, lean, very thin, somewhat awkwardly bent, and this time clutching his folder over his waist with both hands. He has the caught-in-the-headlights look, characteristic of pap shots, but it is the contest between the predatory lens and Grassl’s retaliatory stare that gives the image its unforgettable quality. Here, to be sure, is the Piano Man as something other than the formulaic sufferer of psychiatric illness: a strongly minded figure, pale, and surrounded by leafy green rather than a white room with all the ligature points removed and slumped figures in armchairs watching daytime TV. Far from looking abject in his melancholy, the young man in Gunnill’s most widely circulated image looks closer to the inspired and also tormented figures of Kaspar David Friedrich, Edvard Munch, or August Strindberg in his Inferno period. According to the article published in Pink News on May 1, 2007, Grassl’s last words on this drama before he got on with studying Baudelaire were wishful as well as decisive: ‘That Piano Man stuff, no-one is interested in that anymore.’ He was properly stitched up by the press and its less than authoritative commentators and hirelings. It still seems possible, nevertheless, that, one day, he might look back at that photo and feel just slightly satisfied that he produced an image that kept the snarling (and not just) tabloid contempt for asylum seekers and scroungers at bay for a full season.

Patrick Wright is a writer and broadcaster who teaches at King’s college London. He has recently made a radio documentary about another German visitor to the Isle of Sheppey: ‘A Secret Life: Uwe Johnson in Sheerness’ broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on Sunday April 19, 2015.