Goalkeeper, Brindley Road 1956, by Roger Mayne

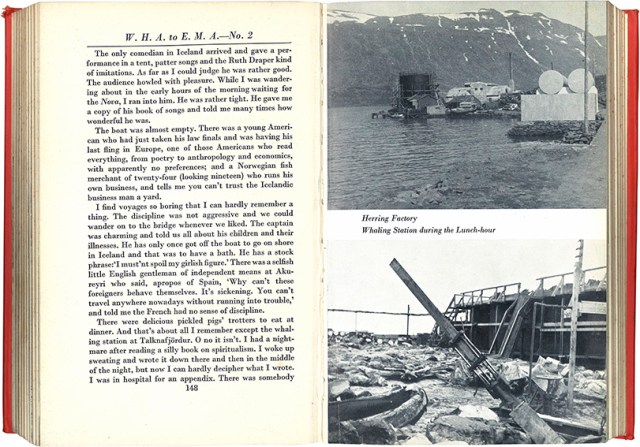

A long time ago I wrote a book about goalkeeping. I tried to persuade the publisher to put on the cover one of the number of Roger Mayne’s street pictures which so eloquently describes the business of keeping goal in games of street football. The publisher refused, saying that something more like the commercial experience of watching sport in a stadium would sell more copies, but still allowed me to put one of Mayne’s on the back cover of the hardback issue [1].

Mayne’s pictures would fall comfortably into a number of the categorisations of photography. They are street photographs, documentary photographs, sports photographs, photographs of childhood… . They have historical interest, social interest, a certain ethnographic or anthropological quality. If one were keywording for a picture library, they would also be filed by the superficial descriptions of the people within them, street names and the wider district, the date, perhaps the type of camera or film used. These overlapping descriptions would place them in a context of other pictures, more or less similar, more or less connected. We are used to this kind of external classification of photographs and use versions of it all the time. That’s how we search on Google, order our hard drives, label archives. It’s completely standard and while individual classifiers don’t always agree, the system itself is beyond question, like the Dewey decimal system for libraries or the SI units.

People write of ‘tropes’ in photography and that seems an extension of the same filing system. The tropes are external categorisations of pictures, even where they are expected (or analysed) to have an internal, emotional effect. So, for a single example from something I was reading recently in another context, Marta Zarzycka discusses the functioning of visual tropes in regard to a particular picture by Samuel Aranda which won the World Press Photo Picture of the Year award in 2011 [2] . The picture conforms to a pietà-like pattern of a grieving or mourning mother holding a son and Zarzycka follows the general usage of the phrase when she writes that “Aranda’s image thus exemplifies the fact that photographic tropes, circulated as evidence of a common perspective or ideal shared by many, may force certain associations and prohibit others, neutralising the local and the particular into the global.”

Since the trope is sometimes used to describe very broad patterns and sometimes very small ones, I often wonder whether it isn’t a word that might better be replaced by different ones according to the context. Trope sometimes means no more than a shared subject of a number of pictures, sometimes a ‘type’ of picture and sometimes a manner of photographing. It is even sometimes used interchangeably with the word ‘cliché.’ But a word which can be used equally in phrases like “the visual trope of the white UN Land Rover” [3] , and “She [Dorothea Lange] photographed African Americans with the same visual tropes she used with whites, representing them as equally hardy salt-of-the-earth farmers – part of the American yeomanry [4] ”, is maybe not isolating a specific phenomenon with any great clarity.

But even if we can arrive at clear language to use, I find myself thinking that this isn’t the way we store photographs in memory and access them for use.

I believe that in addition to a substantial vocabulary of remembered photographs, filed somehow and accessible by their relevant file-tags, most of us also hold within our minds an architecture of access to those photographs which is the reverse of that familiar external system of classification.

There is no difficulty in the more usual system. If I need to recall a picture, say, of great achievement against long odds, I can effortlessly search my mental filing cabinets and come up with Sherpa Tenzing on top of Everest [5], or one of the versions of Khaldei’s view of the Russian soldier on the Reichstag [6].

But that’s reducing photography, as it has so often been reduced in the past, to its role as illustrating tool. I think it’s much more. I think we actually think in photographs. At least some of the time, the tropes are not types or patterns of photographs so much as types or patterns of thoughts that we hold in photographs.

I was, in the past, a goalkeeper. That’s why I wanted to write about it. I was not necessarily at all good as a goalkeeper, but I was sufficiently committed to think like one. I still get into trouble at football matches for applauding the ‘other’ goalkeeper when I see a fine stop, even when all those near me are hoping to see a goal. I admire the athleticism and judgment of goalkeepers, their individuality. I have learnt to some extent to live by the negative scoring whereby a goalkeeper who does something of fearsome difficulty and skill has nothing at all to show for it on the score-sheet and can have it instantly wiped out. I acknowledge the whole complex of this peculiar sport within a sport. As a result, there are large numbers of situations which have nothing to do with goalkeeping that I understand in the terms derived from it. Got to drive a sick child to hospital? Want to make a ticklish presentation to a difficult audience? You’re briefly a goalkeeper, and anything less than utter success is total failure. Member of a group, but not conformable to it? Goalkeeper.

But I don’t think of these things in terms of the words I’ve just written. I certainly don’t think of goalkeeping as furnishing a kind of super-metaphor for many circumstances. I think more in terms of a lexicon of pictures which add up to the metaphorical place that goalkeeping holds in my head. At the centre of that lexicon will be actual pictures of the business itself: Gerry Cranham’s astonishing study of Tottenham goalkeeper John Hollowbread leaping all alone in the murk at White Hart Lane in 1964, Munkacsi’s various studies, the Roger Mayne series. A circle beyond those would be images that help me articulate my view that the world is understandable in goalkeeping terms. These would include studies of movement and grace, but also of despair and disappointment, self-possession, reliability, calculation, membership of a particular subculture, and so on. There is, in another words, not so much a trope of goalkeeping pictures in my head. There is a trope about goalkeeping which governs a certain amount of my thought and can be expressed in pictures.

The point is that I don’t think I’m alone in this. The great difference in Barthes’ formulation of the studium and the punctum, after all, is that the studium is really public and the punctum is really private. We see a picture clearly on a subject or depicting a scene. But we react to it sometimes for reasons which the photographer could not have predicted, often encapsulated in a detail which means something to nobody but ourselves. The public subject and manner of the image, and its membership of a public type of similar images, are given meaning by the private framework into which it lands.

I find some version of this in many different places. David Bate, for example, blends to great effect his personal associations with the public ones in a discussion of Fox Talbot’s 1844 picture of the construction of Nelson’s column in Trafalgar Square and its effects upon him as a viewer [7]. In effect he’s describing the insertion of the Fox Talbot image into a pre-existing complex of ideas of his own, and that I think is exactly what happens. To take another and much more elaborate example, David Campany’s A Handful of Dust [8] is both a brilliantly exciting and unexpected collection of pictures which could only possibly be connected by that one individual through his own private resources; and at the same time a pleasing ballade through some of the best-known and most-discussed theoretical positions in twentieth-century photography. It would be grotesque to look for the entire intellectual contents of Campany’s magisterial exhibition and book in a glossary under the index-word ‘dust’. Yet the process that Campany put himself through – of identifying a host of unmatched thoughts and experiences, many of them wholly personal, then ‘fitting’ them to the more public history and ontology of photography – is in effect the indexing of that section of the contents of his mind. The whole rich mess of ideas which I think of as the trope became, under his careful self-scrutiny, catalogued under ‘dust’ as its cipher.

Campany chose to open A Handful of Dust with this epigraph from W.G. Sebald: “A photograph is like something lying on the floor and accumulating dust, you know, where these clumps of dust get caught, and it steadily becomes a bigger ball. Eventually you can pull out strings. That’s roughly how it is.”

So I’m complaining here that the word trope is sufficiently imprecisely used to mean not very much in photography (or at least to demand care in its handling), and yet I am adding in the same few lines still another meaning to the bundle. That’s absurd. As I wrote further up, I think that a trope is in effect the complex architecture of access to thoughts that individuals hold in memory in pictorial form. It is rarely articulated in words precisely because those words tend to make supple and fluid globs of feeling and memory rather more rigid. To thoroughly articulate a trope in words is to make the effort that Campany made in A Handful of Dust, impractical for most conventional references to the pictures in one’s head, even if not beyond the abilities of most. It’s like the phenomenon of the mental caption: when one can reduce a photograph to a single one-liner, a caption in mind, it becomes increasingly hard to remember the detail of the picture, since it is so much easier to file words in one’s head than pictures. Without a caption, we’re forced to keep the picture ‘live’ in memory, subject to re-evaluation and under constant challenge from the other ideas and pictures it comes up against. So the tropes that make up so much of our visual lexicon of the world. They exist. All of us have a number of them. Yet the minute they are indexed into clumsy single words, they lose their lovely flexibility and strength, and become planks or bricks – useful enough, but necessitating accumulation along predictable angles and lines.

————-

1 Hodgson, F., Only the Goalkeeper to Beat, Macmillan, 1998.

2 Zarzycka, Marta, The World Press Photo contest and visual tropes, Photographies Vol. 6, Issue 1, 2013.

3 Smirl, L., Building the other, constructing ourselves: spatial dimensions of international humanitarian response. International Political Sociology, 2(3), 2008.

4 Gordon, Linda, Dorothea Lange: The Photographer as Agricultural Sociologist. Journal of American History vol. 93, issue 3, 2006.

5 The picture, by Sir Edmund Hillary, is credited to the Royal Geographic Society.

6 I discussed this picture a little once for Bonhams magazine: Bonhams Magazine, Issue 41, Winter 2014, Page 38. Many other scholars have discussed it at greater length.

7 Bate, David, The Memory of Photography, Photographies, vol. 3, Issue 2, 2010.

8 Campany, David, A Handful of Dust, MACK/Le Bal, Paris (and London), 2015.

————-

Francis Hodgson is the Professor in the Culture of Photography at the University of Brighton.