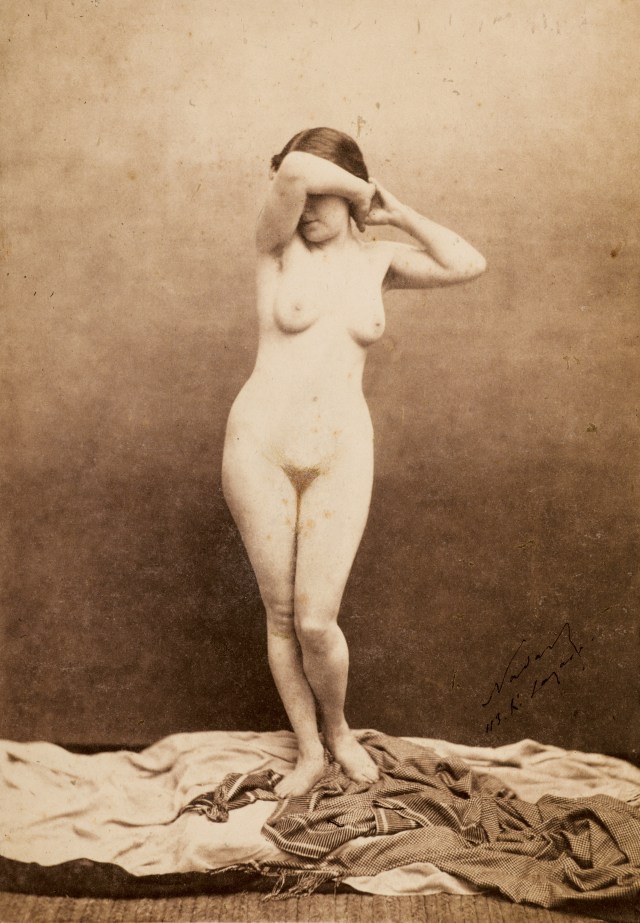

Mariette, by Félix Nadar (Gaspard Félix Tournachon, 1820-1910), c. 1855. Salted paper print from a glass plate negative (210 x 147 mm), Wilson Centre for Photography.

Mariette presents us with first photographic principles. Created by French photographer Félix Nadar in Paris, sometime around 1855, it is currently on display with over 90 other salted paper prints at Tate Britain.

Walter Benjamin, in his A Short History of Photography in 1934, described these early prints as ‘incunabula of photography’. For Benjamin, these had quickly been superseded by an industrialisation of the medium, extending into his own century, but were the ‘first flowering’ that pointed the way for photography in the future.

Nadar’s print Mariette catches the experiment of early photography. He made the negative image on a glass plate coated in a viscous solution of collodion and light-sensitive silver salts, a process barely five years old, and printed it as a salted paper positive, the earliest photographic reproductive method, introduced by Henry Fox Talbot just fifteen years before.

Very soon, as Benjamin explained, improved optics and finer albumen prints ‘conquered darkness and distinguished appearances as sharply as a mirror’. Photography lost the balance of dark and light intrinsic to the relatively simple response of chemicals to shadow and illumination. Mariette’s pose, graphically white against modelled umbers, retains the sense that ‘the light wrestles its way out of the dark.’ The texture of the silver salts caught in the paper fibres subtly softens and equalises the contours, so that they echo one another across the image. Benjamin argued that a longer pose created a less spontaneous, more accumulated, synthetic likeness. Figures were, moreover, observed in an open place where ‘nothing stood in the way of quiet exposure’. As a result, Benjamin believed, ‘they live, not out of the instant, but into it… they grew, as it were, into the image.’

In our age of photographic celebrity, from Instagram to 24 hour rolling news media, it is interesting to reflect on Benjamin’s observation: ‘for these first to be photographed, the viewing space went un-framed or, rather, uncaptioned.’ Mariette resists framing, still. The woman who stood in front of the lens was Marie-Christine Roux (1820–1863), also know as Marie-Christine Leroux, a professional model who earned her living in the ateliers of Paris. Her career ended in 1863 when she drowned in the wreck of the Atlas, a steam ship on the way to Algiers. Mariette was the name given to a fictionalised version of Roux by her ex-lover, the writer Jules Champfleury, in Les Aventures de Mademoiselle Mariette (1853). She is also identified as Musette, an earlier fictionalised account of Roux, in Henri Murger’s short stories, Scènes de la vie de bohème (1851), which became the basis for Puccini’s opera La Boheme (1896). Nadar’s brother, Adrien Tournachon (1825-1903), made a portrait of Roux as this character.

Murger and Champfleury’s precocious tales of modern life aspired to the realism of photography. Their fictional Musette and Mariette played out tensions between real and false representation in the form of real and false love. Affairs were undone by the women’s ambition to earn money; their modelling was aligned with prostitution and their affections were shown to be sham. This tangle of life and art, truth and artifice, manifested itself in Nadar’s photograph of Roux posing naked before the camera. It registered a more open and inscrutable reality, however. Mariette reveals her body and covers her face. Hope Kingsley has pointed out that this may have been a precaution against censorship laws which could sweep up models in the prosecution of photographers for pornography. Roux’s pose also reflected contemporary anecdotes about models and courtesans concealing their identity to hide the means by which their apparently respectable bourgeois lifestyle was achieved. It was a time of broader anxieties about the way modernity, and technical and demographic changes in the city, were confusing clear class and moral boundaries and the difficulty of distinguishing these from appearances alone.

Mariette was one of the first paper photographs to represent the figure unclothed. The covered face removed it from the realm of the portrait to the nude, entering photography into its long dialogue with the conventions of the painted and sculpted nude. At the same time, it established the modern media’s distinctness from painting and sculpture. Roux’s contrapposto stance, with all her weight on one leg, is close to that of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ (1780 – 1867) life-size nude La Source, which was exhibited in 1856, on which he was working at the same time. Ingres was well known to both Nadar and Roux: she posed for the painter, and the photography historian Helmut Gernsheim has suggested that the photograph was taken for the purpose of being painted. In Mariette, the element of exposure intrinsic to the photographic method is expressed in its more stepped back, empty perspective and the expanse of drapes apparently dropped at the figure’s feet. In comparison, Ingres’ figure raises her arm to support a vessel of water and with her distracted gaze appears unaware that she is watched, while the contradictory combination of Roux’s defensive arm and her frontal stance are united in their acknowledgement of the lens.

A few years later, in 1861, another painter in their circle and customer of Roux, Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824 –1904) purchased a print of Mariette. He adapted it for three paintings. The first was Phryne Before The Areopagus. Phryne was a model and courtesan from classical times, the legendary muse of the painter Apelles and the sculptor Praxiteles. The painting showed her before a court on charge of impiety. As a last resort, her lawyer was said to have bared Phryne’s breasts to the judges, and thus secured her acquittal. Nadar’s photograph was ideal for this subject, but Gérôme raised the defensive arm slightly to reveal Phryne’s shadowy eyes, to hint at an acquiescent gaze, and diluting the image to something more permissively painterly. The modern resonance of Gérôme’s central motif, the model dissembling respectability, was not lost on contemporaries, however. ‘This skinny, knock-kneed Phryne’, one critic wrote, ‘whose flat hips still bear the mark of the corset, just as her legs show the line of her garter, and who is nothing but a brazen wench.’

Phryne’s marble-like flesh is immaculate. The modernity the critic speaks of, a degraded modernity in his eyes, is that of the photograph, what Benjamin called ‘the spark of accident’. ‘All the artistic preparations of the photographer and all the design in the positioning of his model to the contrary, the viewer feels an irresistible compulsion to seek the tiny spark of accident, the here and now. ‘ An indentation left by a garter can be seen on Roux’s calf. Her underarm and pubic hair depart from the conventions of the smooth skinned classical nude (Nadar had tidied the latter on the negative before printing). Roux’s knees are knees that bend, that have sinews and tendons emphasised by her contrapposto position. That indexical presence is continued in the fabric, an inconsequential but nonetheless impossibly complex distribution of mass and movement settled on the fine texture of the rush mat, beyond the skills of any draper painter. ‘Something remains that does not testify merely to the art of the photographer, something that is not to be silenced, something demanding the name of the person who had lived then.’

‘These images were taken in rooms where every customer came to the photographer as a technician of the newest school,’ Benjamin wrote, while ‘the photographer, came to every customer as a member of a rising class.‘ Roux was not strictly a customer, but Mariette emanates from model and photographer – each of them, incidentally, 35 years of age – negotiating the professional, technical, artistic and social change of their times. This intersection of method, medium and moment was what Benjamin called the aura: ‘For that aura is not simply the product of a primitive camera. At that early stage, object and technique corresponded to each other.’

Salt and Silver: Early Photography 1840-1860 ran 25 February – 7 June 2015 at Tate Britain.

Carol Jacobi is Curator of British Art 1850-1915 at Tate Britain.