This photograph is a work of fiction. The young man in the white jacket is not a strangler; the older man in the darker coat and glasses is not his victim. The truth, in fact, is the opposite of the depiction; the younger man was the victim. He is the one in pain. The empty expression on his face does not indicate the affectless, anhedonic emotional vacuum of the psychopath, but the broken, stupefied, resigned condition of the tortured. His name is – or was – Kristjan Vidarsson, although, at the moment of the photograph, he probably couldn’t recall, with any conviction, even that.

*

On the night of 26 January 1974, the wild Reykjanes peninsula in Iceland was battered by storms. Gudmundur Einarsson, an 18-year-old labourer, had been partying in a harbour town south of Reykjavik, six miles from the home to which he never returned. The search for his body was called off after a few weeks; disappearances are not that uncommon in the more untameable parts of Iceland. 10 months later, in November, Geirfinnur Einarsson (no relation to Gudmundur), received a phone call summoning him to a harbour cafe. He never returned home either, and an extensive search of the harbour uncovered no body.

And no evidence, nor no witnesses. The two men seemed slurped into a black hole. Rumours, as they often do, abounded, concerning a small-time crook who had been arrested for smuggling cannabis from Denmark called Saevar Ciesielski. In December 1975, he and his girlfriend, Erla Bolladottir, were arrested for an unrelated minor crime and the police, for reasons unclear, asked Erla questions about the disappearance of Gudmundur and Geirfinnur. She recalled the night that the former had vanished; she remembered the fierce storm and the peculiar nightmare she’d had in which Saevar and his friends were whispering in low, conspiratorial voices outside her bedroom window. The head of the investigation, on hearing this, told her: ‘we are going to help you recall everything and you will not be able to leave here until you tell us what happened to Gudmundur.’

Consider, now, this scene, of which no photographic record exists: Erla alone in her cell, sleepless. Erla fretting over her 11-week-old daughter. Erla in an interview lasting 10 hours during which dreams and memories and cravings to return to her normal life intermingled. Maybe she could recall a body wrapped in a sheet. Saevar in solitary. Saevar, under interrogation, mentioning three friends: Kristjan and Tryggvi: both arrested and isolated and endlessly questioned. And Albert, a gentler figure than the other two and whom the isolation and the interogations quickly broke. He admitted to hiding Gudmundur’s body in the lava fields. Could Geirfunnur be there too?

Enter phantasms, fanciful imaginative flights, chimeras from hysteria: perhaps Iceland had its own Mansonesque death-cult. Its own underground psychopathic separatists, with Saevar as their Charlie. Erla, again under interrogation. Geirfinnur fell off a boat and drowned; no, he didn’t, he was murdered on the boat then thrown overboard. No, no, he was killed on the dockside after he failed to deliver promised booze. His body was burned in the lava fields, that mad dreamscape where sprites and goblins made the laws. The suspects, whose foggy and piecemeal recollections gave the police such stories had, by this time, been in solitary confinement for six months.

But evidence – the police required evidence. They brought Karl Schutz over from Germany, who had recently cracked the Baader-Meinhof gang. He set to ferreting out the ‘foreigner’ that Saevar and Kristjan, in their ramblings, had mentioned, and found Gudjon Skarphedinsson, Saevar’s accomplice in cannabis smuggling; an Icelander, yes, but of swarthy complexion: in such ways does the carcerally bureaucratic mind, in a fervid search for corroboration, find its own facts. In solitary confinement, Gudjon was given relaxants and sleeping pills. He was the second to break, after Erla. Over a period of two years, the suspects were taken out to the lava fields 60 times. 60. Even without evidential proof, Schutz branded them as ruthless, merciless, rapacious people. Capable of killing. He had – because he needed to have – his perps. Later, they withdrew their confessions, but the verdicts were found and the sentences delivered: life imprisonment for Saevar, three years for Erla, 12 for the others. Redress for crimes to which they confessed but which they could not remember committing. The mind finds its own facts.

*

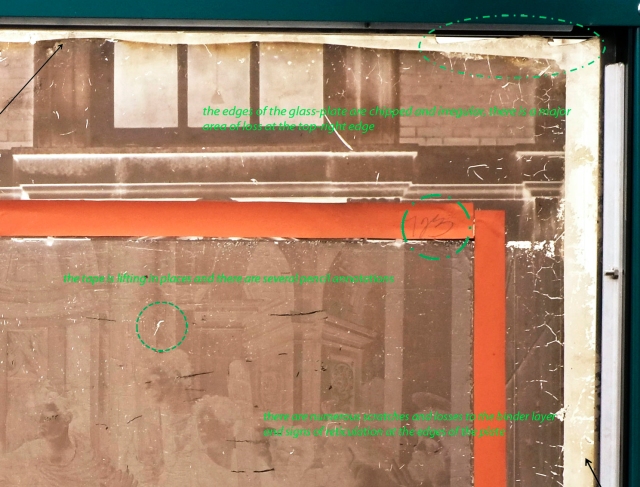

Gisli Gudjonsson, an ex-detective, is now a forensic psychologist and a leading authority on False Memory – or, as he preferrs to call it, Memory Distrust Syndrome. He points out its main triggers: isolation, persuasive interrogation, false evidence, high emotional intensity and the external insistence on the futility of continued denial. Concerning the false evidence, there’d been rumours of a set of photographs, kept in Iceland’s national archives, one of which showed Kristjan strangling a policeman playing the part of Geirfinnur. Another showed Kristjan standing next to a dummy playing the part of a corpse. Gisli: ‘once you have enacted something, it then becomes more of a reality.’

See Erla in isolation for 105 days, away from her infant daughter. See her being interviewed over 100 times, only on three occasions with a lawyer present; often these interviews went on for over 12 hours. There are no photographs of this. Now see Saevar with his head held in a bucket; effectively being water-boarded. See him and the other suspects deprived of sleep, company, air. There are no photographs of this. See Tryggvi in solitary confinement for 655 days. Doped with Diazepam and Mogadon. See him, along with all the other accused, cleared, in 2011, after an 18-month inquiry. Says Erla: ‘the case is a body that keeps rising out of the grave.’ Gudjun, now a retired Lutheran minister, expresses bafflement that he confessed to a killing he had no memory of carrying out. And he also, still, in his broken English and in his broken voice, expresses doubts: ‘if you have been telling someone where he has been, what he has done, telling him that other people were involved, in the end you can say him to be in the same position as you want to have him. He does not have any more his memory or the power to say no.’ And Tryggvi and Saevar? They’re saying nothing. Tryggvi died in 2009, at 58. Saevar died in Copenhagen, homeless, two years later. He was 56.

*

Korsakoff’s syndrome is a type of dementia associated with excessive alcohol consumption and which generally causes deficits in declarative memory. Sufferers find problematic, if not impossible, the processing of contextual information, which is an essential component of accurate recollection, resulting in gaps of memory which are plugged with confabulation. I’ve seen this at work; alcoholics asking me if I remember the long weekend we spent at a zoo, or in Toronto, or whatever – invented memories, fictions, necessitated, in part, by the need to arrest the dissolution of identity, crucial to which is the recall of individual experience. Deeply saddening to witness.

As this is an era of manufactured need, so too is it an era of manufactured illness. Are we suffering from Korsakoff’s too? Is our collective memory full of holes? For instance; did we really see that photograph of the Bullingdon Club, the epitome of unearned privilege? David Cameron and Boris Johnson have forbidden its reproduction, this we know, but in their airbrushing of their own histories is the undermining of our own. How well do we recollect that image? Did we even see it at all? And what The Sun blatantly and imperiously demands us to accept as ‘THE TRUTH’, well, it has taken a quarter of a century for the Hillsborough Commission to prove that the headline would better have read ‘THE LIES’. That image of the crouching fan with his hand in the pocket of the prone and unconscious figure, he was not seeking valuables, as we are told; he was looking for a way to identify the dead, to contact the next of kin. And those sodden corpses; yes, they were drenched in urine, not because the living wished to vilely desecrate the dead, but because human beings, whilst being crushed to death, have a tendency to piss themselves in agony and terror.

This is Korsakoff’s syndrome foisted on the non-alcoholic and the sane. This is dementia imposed from without. It is a lover scissoring the ex out of the photograph of happier times in a fit of jealous rage and insisting she was never there in the first place. Susan Sontag, in Regarding the Pain of Others, wrote that ‘one of the characteristics of modernity is that people like to feel they can anticipate their own experience.’ How possible is that if we cannot remember our own experiences with any conviction or confidence?

The contemporary human is unanchored, unmoored, adrift on a sea of ostensible experiential corroboration, none of which can be trusted. Spectacularisation – or one aspect of it, namely the external concretisation of shared experience and data – to Debord, was illusion, and to Baudrillard, it was all hoax. Sontag has a more positive spin: ‘There is still a reality that exists independent of the attempts to weaken its authority. The argument is in fact a defence of reality and the imperiled standards of responding more fully to it.’ Yet even such a concept as ‘reality’, in this context of tangible proof, of irrefragability, becomes unreliable, or, rather has been made so. This is not Photoshopping, or CGI on Youtube; this is the powerful making insubstantial and untrustworthy of the living bedrock. This is, in effect, allowing reality to be constructed by self-serving arbiters. The world is what we are told it is, not what we perceive it to be, and the ontological reinforcements of physical record and artefact are themselves fictitious. So Gudjun still feels, three decades on, that he ‘does not have any more his memory or the power to say no.’ Look, here’s Kristjan frozen forever in the act of murder. Memory is elusive and slippery; hard images are not. What will you trust?

And how we wish we could dismiss as false certain images that we know to be more or less objective truths. As a child, searching through bundles of damp-swollen and half-rotten books and periodicals in a relative’s garage, I came across a copy of Ernst Friedrich’s War Against War!. How I wished then, still wish now, and will forever, that the mounds of mutilated corpses displayed on its pages were just mannequins, or that those appallingly shattered faces were due to make-up and prosthetics. That they were just particularly gruesome Hallowe’en masks. And I am reminded of the recent campaign in Liverpool to re-christen those streets to which slavers gave their names; an understandable impulse, yes, but we have the history we have, not the one we would like to have. Unless, of course, the power is available to edit one’s own history, to transmogrify truth into lies and lies into truth, eroding the quiddity of such concepts in the action.

I wonder about Kristjan, and whether he was sure – as much as anyone can be – of who he was as he lived rough in Copenhagen; whether he really knew that he was not a killer of other human beings. Whether his innocence in that matter was felt as a fact in his heart, and in that part of his brain where certain self-knowledge resides. Whether, at the moment just before hypothermia wiped everything white, he yearned for forgiveness or craved redress; or whether his sense of self had been so steadily and systematically dismantled that even the wellspring from which such longings should sprout had been filled in, occluded. Choked. I hope he knew, at the last, that the only truism attached to his story – and the wider world which it metonymises – is this: do not trust what you are ordered to trust. Whatever you are told is true might be a lie.

Niall Griffiths is an English author of novels and short stories, set predominantly in Wales.